Let me start out by putting this piece into the cultural context of the United States. Incarceration has achieved all-time high levels in terms of our own history, and in a global context as well. According to the US Bureau of Justice Statistics (in 2013 reports): 2,220,300 adults were incarcerated in US federal prisons, state prisons, and county jails–which constitutes about 0.91% of adults (1 in 110) in the U.S. resident population. This number is truly astronomical, and there is no doubt that the structure of the system itself has been questioned by many. One way we begin to better understand the issues, doubts, politics, and realities of the U.S. prison system is through looking at artists, scholars, and activists who have attempted to capture life behind bars, and report back from the field.

Jimmy Fishbein captured life in the Louisiana State Penitentiary as a part of his personal photography series. To give a little background, LSP, which is also known as “Angola,” is a maximum security penitentiary in Louisiana. It also happens to be the largest maximum security prison in the U.S. to-date, with approximately 6,300 prisoners. The property is a massive 18,000 acres—and is named after the former property, “Angola Plantations”, that used to sit upon it (named Angola, for the country the slaves who worked on it originated from). Over 85% of the prisoners at LSP are serving life sentences.

"I hate the way men become useless over time in prison" --Jerry Brown (LSP inmate)

Fishbein’s project is one of many that uses photography to capture the lives of inmates, especially those sentenced to life without parole—or rather, sentenced to death. In fact, LSP has been the subject of many photographer’s personal projects. Benjamin D. Weber, an Adjunct Professor at the University of New Orleans, collected stories from prisoners at LSP who had lost a loved one during their time in prison, and created a website which documented these stories using both text letters, photographs, and maps to depict memories these inmates wanted to share with the world—he entitled his project, “Stories from Prison / Honoring Ancestors.” Weber and his undergraduate students actually performed the commemorations that the prisoners requested, to honor the lives of their ancestors when they could not themselves.

Others, like Pete Brook, who has started a project on prison photography, derived their interest from scholarly pursuits. Achieving his master’s in museum studies at the University of Manchester and then moving to California, Brook became interested in prisons and prison culture after moving to the United States. His work has taken a historical, cultural, and artistic approach—looking first at the expansion and emergence of prisons in the United States and then traveling across the country himself looking at photographers who were working with prison inmates as portrait subjects. A subsequent project (other than his primary academic interest) was developing a Prison Photography blog, where he has documented the interest of other photographers in capturing life in prison, and explored what these kind of projects actually do in popular media and social sharing. In speaking with LENS, a photography segment of the New York times, Brook claimed:

“It fascinates me that there is a prison system with 2.3 million people in it and no one seems to see that as a problem. At what point was that normalized? After the prison population was quadrupled in 30 years, when did everyone accept that as O.K.? At what point did the alternatives not matter and not get to the table?”

From: prisonphotography.org; Pete Brook's Prison Photography Blog

Photography projects have emerged alongside of a desire to understand and perhaps advocate for the transformation of the criminal justice system, it is a subject gaining a great deal of attention in academic circles and beyond. Dr. James Kilgore, a professor based at the University of Illinois, argues that legislative action ultimately holds the key to change in this system—and that this can be achieved with bipartisan efforts. His recent book Understanding Mass Incarceration A People’s Guide to the Key Civil Rights Struggle of Our Time has been called a “An excellent, much-needed introduction to the racial, political, and economic dimensions of mass incarceration” by Michelle Alexander (an associate professor of law at The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law; a civil rights advocate and writer). This text is ground-breaking in the sense that it describes and problematizes the criminal justice system in an accessible way—something not just intended for an academic audience, while still maintaining scholarly rigor and a deep exploration into this convoluted cultural phenomenon.

When asked about prison photography, and why these projects have worth and impact, Pete Brook told the New York Times:

“Well, a lot of people don’t want to talk about prisons. There’s no incentive for anyone in society to look at prisons for the failure that they are. Politicians don’t win if they appear to be soft on crime. And then you have the media, which is after ratings. It wins by stoking up emotions. With ‘American Idol,’ it’s making people sentimental. With politics, it’s making people divided and angry. And with crime, it’s making people afraid”.

Of course, different photographers who take on these prison-based projects have different motivators that inspire, and they hold different stakes. Deborah Luster took portraits of Louisiana State prisoners for their loved ones,to capture themselves as they would like to be portrayed—in the setting, with the object, or using the expression that they personally felt represented their own bodies and circumstances, as an act of both communication and explanation. Each prisoner also chose what supplementary information they wanted used alongside their portrait, such as their inmate number, date of entrance, place of birth, tattoos, birth date, sentence, or whether or not they had children. Luster left this up for them to decide. Jamel Shabazz, who is thought of as an icon in New York, and has achieved major commercial success, actually worked as a corrections officer at Rikers Island for 20 years. In one of his more famous prison photographs, “Lock Down” Shabazz places himself in a cell with a defendant who was awaiting a court hearing. As someone who worked so closely with the prison system, his photographs take on a unique perspective:

From: Deborah Luster's Photography Website

From Casimir's Website

“Throughout my career I would often place myself in this same cell to be reminded of how my life could have been drastically different if I had not made the right choices.” —Jamel Shabazz

These are just a few of the many projects that have been grounded on an interest in criminal justice space—whether for advocacy, art, capturing subjectivity, or social awareness. Just as these photographers capture a certain dimension of life in prison, so to does Jimmy Fishbein capture individuality in portraits of inmates in the LSP. After his shoot at the LSP Fishbein finds prison to be a surreal experience. In speaking with me about the shoot he stated that these prisoners:

“Fucked up at one moment and now they are paying their entire lives. It bewilders me. I don’t know why I feel that way but, one mistake changed their entire lives”

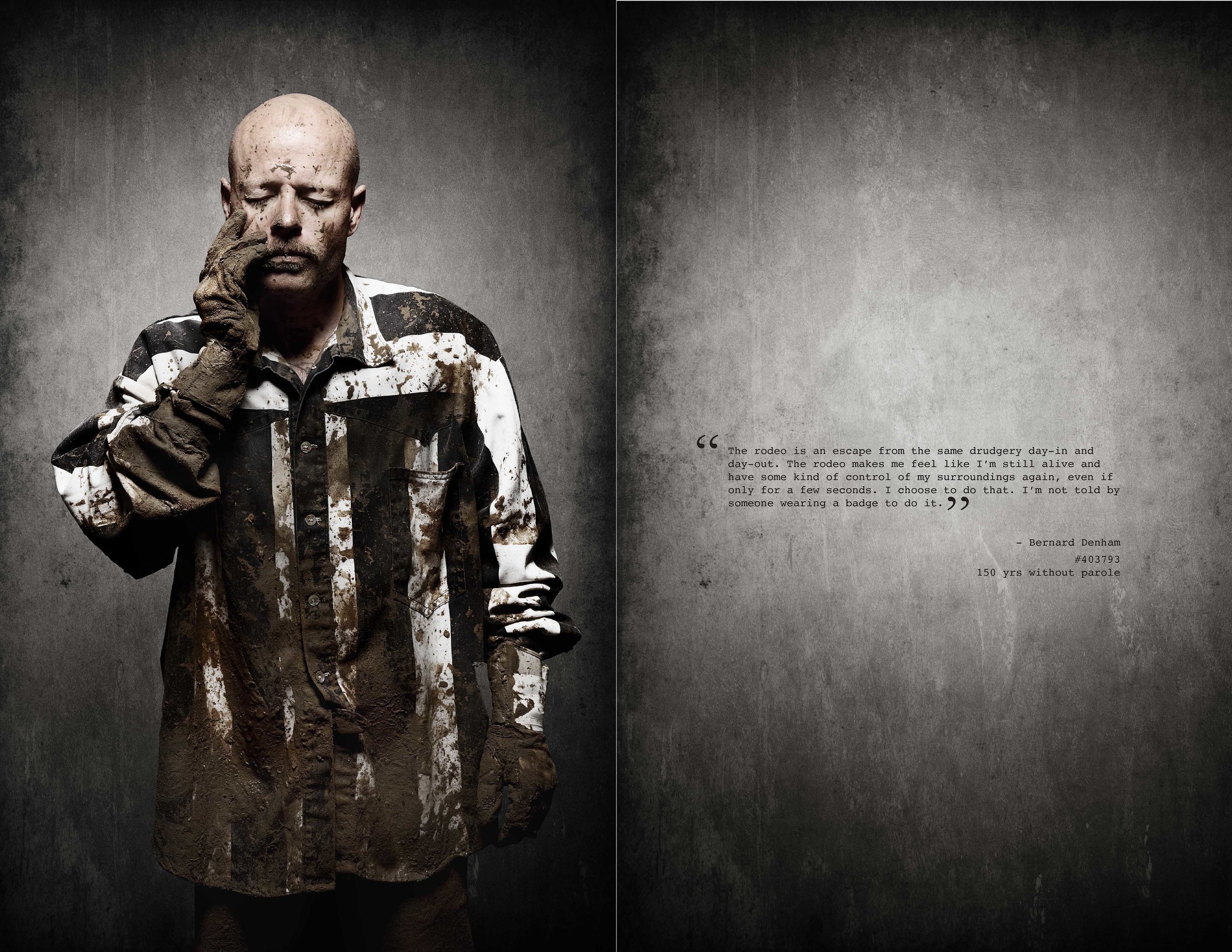

In addition to capturing portraits of some of the male LSP prisoners, Fishbein also had a chance to attend and photograph the rodeo which is held once a year. It is one day out of the year that prisoners get to let loose, get out, and be apart of the local community. Only the prisoners with the best record are allowed to participate—that means a clean record for a year gets an inmate one day to participate and be a part of a community event. It allows for a certain amount of release for these individuals, a moment to play and feel a sense of freedom. Fishbein noted that these individuals wore no helmets and no protection, and that he felt it gave these men the opportunity to feel real, physical pain.

"The rodeo is an escape from the same drudgery day-in and day-out. The rodeo makes me feel like I'm still alive and have some kind of control of my surroundings again, even if only for a few seconds. I choose to do that. I'm not told by someone wearing a badge to do it." --Bernard Denham (LSP Inmate)

Behind bars, 2,220,300 American adults are living their lives--which is nearly 1% of our country’s residential population. That prodigious number has certainly inspired a close look into our criminal justice system by academics, journalists, photographers, artists, and popular media. Often, inmates are cloaked in a veil that does not allow them to be seen. They are criminals removed and segmented from society at large. Truthfully, this veil serves many purposes: an illusion of safety, a system of law and consequential social order which does not need to be seen or discussed by the law-abiding, and, of recent interest, inmate labor and production. However, even if just for a moment in time, prison photography creates a window on behalf of those behind the curtain to shine a light on the lives that are being lived behind bars.

By: Megan Melissa Machamer

MA Social Science, University of Chicago

BA Sociocultural Anthropology, UC San Diego

Megan Machamer is a sociocultural anthropologist who develops creative commentary for the Jimmy Fishbein photography blog. Her perspective as a social scientist contributes additional dialogue to stand-along photography and serves as one perspective to evoke thought and conversation upon viewing these photos.