Many were surprised at the outcome of the 2016 election season, not just in Chicago, but all over the world. This has been, by-far, one of the most interesting and challenging political seasons to get through. Many expressed the notion of just wanting election season to be “over,” but it turns out that having a result and an end to the election has not been the outcome that many were hoping for—and that is especially visible in urban liberal spaces across the country. In the last few weeks, Chicago has seen a noticeable upheaval with those frustrated, saddened, and angered by President Elect Trump’s defeat of Hillary Clinton in the election. Although Clinton won the popular vote, the electoral college ultimately allowed Trump to prevail.

This was a particularly upsetting win for marginalized groups who were directly insulted by Trump during the 2016 campaign. This includes but is not limited to African American individuals, women, and especially women of color, Muslim Americans, immigrants, refugees, Mexican-Americans, Latinos, and those who identify as LGBTQ. Many saw various offensive moments of the campaign as being “the end” of Trump—especially moments like his leaked video, ultimately proclaiming that sexually abusing women without consent was okay. A significant amount of individuals, affiliated with both democrat and republican parties, believed that these remarks would certainly disqualify Trump from the presidential race. Hoping for an “end” to the political season was, for some, partially because of the frustration associated with these various moments in the campaign. However, America voted, and it appears that these instances of clear bigotry were not enough to disqualify Trump for the highest ranking office in the United States.

This was not an election which centered on debates of policy, and rather, candidate discourse, decisions, and worldview. It’s focus on the dichotomy of social outlook between the two parties is ultimately, at least in this anthropologist’s opinion, why the post-election protests are particularly striking, visually and rhetorically, for this 2016 election. It is not necessarily that Americans are upset that a republican candidate won the presidential election—it is the values, dialogue, and contempt openly reflected in this particular candidate. The public reaction is not to the ideologies of republican party, it is directly to President Elect Donald Trump.

As with any major political moment, popular culture is a good place to begin looking for meaning and a better understanding of popular opinion. Commentary like the recent Saturday Night Live skit, “Election Night,” echoes another sentiment—that perhaps we should not be surprised at all that Trump was able to win the United States election. It is a comic portrayal of a very serious point: that America at-large remains racist, xenophobic, and sexist as ever. This is a frustrating point, but still one that we need to try to wrap our heads around for any kind of social progress. While people were saddened, scared, and frustrated by the election results, and took to social media, TV broadcasts, radio, and open protest in the streets to demonstrate this collective affective sentiment—perhaps the reaction to the racism, sexism, and discrimination that was a part of pre-election discourse was not one which should have amplified being “blind-sided.” Maybe the shock and embarrassment demonstrate should not have been as prominent in the vocalizations, in consideration of American politics and sociopolitical climate as it stands today. These issues have been all too real for the communities that they impact the most, and while angering and frustrating to see an openly discriminatory candidate win an election, perhaps the fact so many would vote for a candidate with these values should not be ground-breaking “news.”

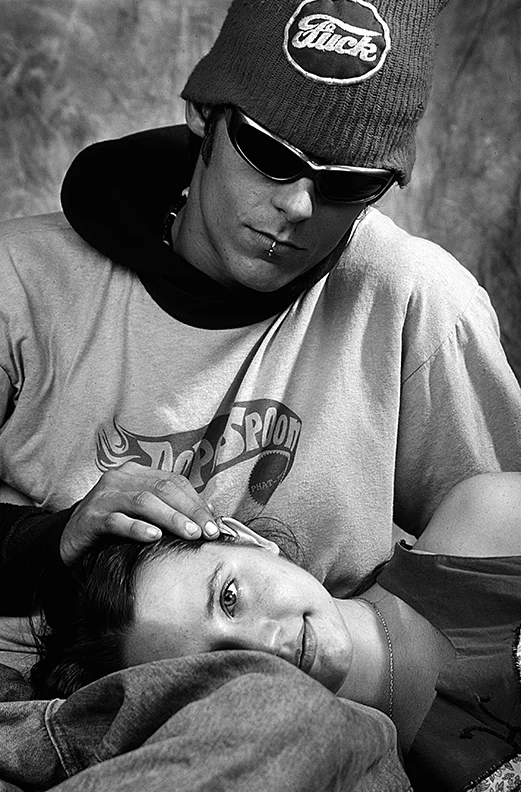

I’ve been trying to figure out how to put the stream of social media posts, fake news articles, journalistic reactions, social science discussion, and informal conversations that I’ve encountered into a post that anyone at home or abroad could relate to. It is difficult to take the “next step forward” or “onwards and upwards” approach in this article. It also does not feel right to live in denial or total angst regarding what is currently happening in American politics. When Jimmy Fishbein went to photograph the protesters at Trump Tower, right in the heart of River North, Chicago, I realized their reaction was all I needed to explore—a state of refusal, voices of anger, and yet, a communal feeling of togetherness and hope that individual voices can in fact make a difference, or at the very least, an impact.

One of the aspects of democracy that binds America together is the notion of “free speech” and the right to openly protest. The feel of the city immediately following the election, was definitely one of resentment and immediate action. While there is always one “losing” party in the U.S. with our bipartisan system, something felt different about this election. Presidential elections always involve value systems and beliefs that extend beyond political economic views and governance—but with Trump’s particular bigotry and distain for various human groups, many people took this election victory as a personal attack on their cultural background, sexuality, gender, or religious beliefs. These aspects run deep in an individual’s human experience.

Protests have continued in Chicago, and they will likely continue into the new year as well—witha march planned for inauguration day. Many question if these kind of protests and forms of public display actually end up doing anything in the long-run. People are left to wonder if hope is totally lost for the U.S. with this particular republican win, or if we are going to be able to move forward and still see the kind of social changes we thought were going to be on the horizon for 2017.

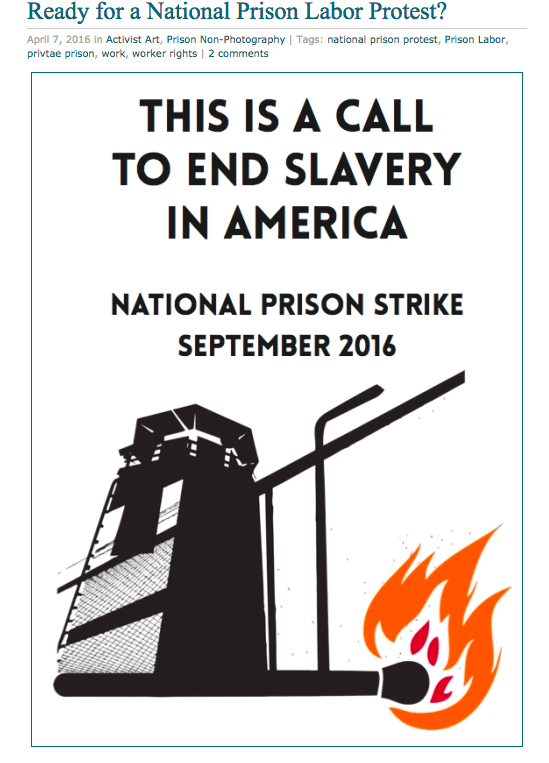

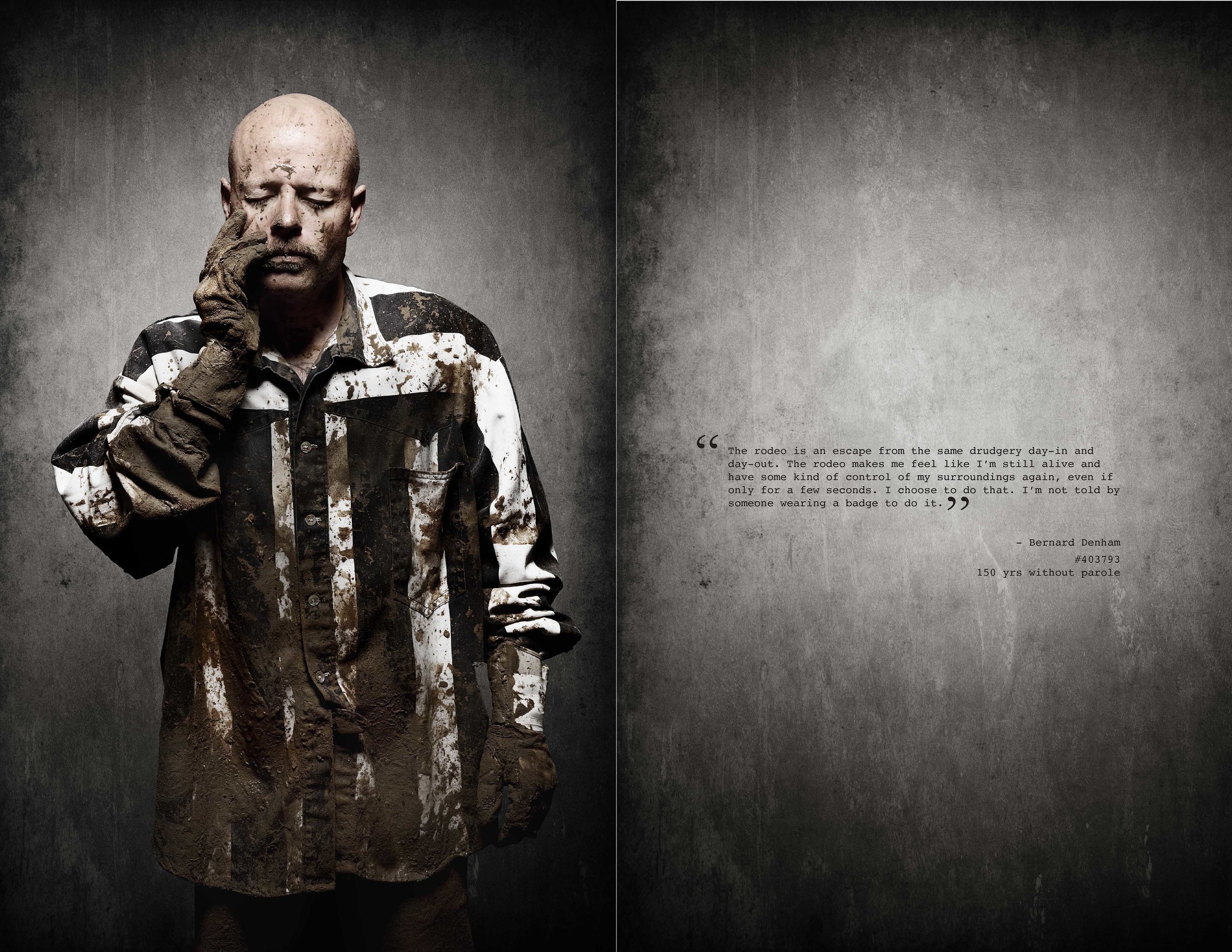

Let’s take a moment to reflect on some the most important protests, movements, and forms of activism in the U.S. over the past 100 years. I have found that looking at these has certainly shown a glimmer of hope into what seems to be an uphill battle. What does the act of protesting do? In the moment, it may seem like a hopeless battle for those pushing for change and acknowledgment of the problems that surround this political decision—but it is important to remember that all major forms of activism have taken time, effort, and countless hours of energy to achieve results. Change rarely happens over night, which is why efforts that may seem fruitless in the beginning may end up being worthwhile in time.

Protesters of Trump’s presidency are really looking to continue what all of these movements are fighting for. Meaning that what these protestors are standing for really encompasses movements for women’s rights, sexual freedom, equal pay for equal work, civil rights and especially the fight against racial discrimination, and equality and fair treatment of LGBTQ members of our community. They are fighting for the safety and rights of refugees and those seeking a better life in the U.S. post-migration. They are fighting for a world, socially, which is brighter and filled with more opportunity for our children’s generation. To me—this could not possible be a more worthwhile fight. While we do have to accept the outcome of the election, and ensure a smooth transition of power, we do not have to accept the social worldview that Trump embodies. We do not need to accept that a president and their supporters can determine the social and political future of the United States, we all have a voice, we all have the opportunity to oppose these views and protest normalization of Trump’s vision for America.

By: Megan Melissa Machamer

MA Social Science, University of Chicago

BA Sociocultural Anthropology, UC San Diego

Megan Machamer is a sociocultural anthropologist who develops creative commentary for the Jimmy Fishbein photography blog. Her perspective as a social scientist contributes additional dialogue to stand-along photography and serves as one perspective to evoke thought and conversation upon viewing these photos.