Photography, film, and other forms of visual art have supported a fascination with capturing struggling subjects. While it presents the world in all its variety, depicting human conditions not always visible to those in the most privileged of situations, it has also been critiqued for exploitation and exoticization of “the Other.” By acknowledging this critique we are allowing for a deeper exploration of why this photography carries meaning to both the photographers that take these pictures and present them to the world, and the way this media is consumed by the viewer. Homeless photography is one of many forms which use imagery to show the life circumstances of subjects in a particular walk of life. By briefly examining the situation of homelessness in the United States, photography projects that have focused on it, and opinions of this art form—we can discuss the critique more fully and begin to unpack the ways these photos depict subjects as a form of conscious social representation.

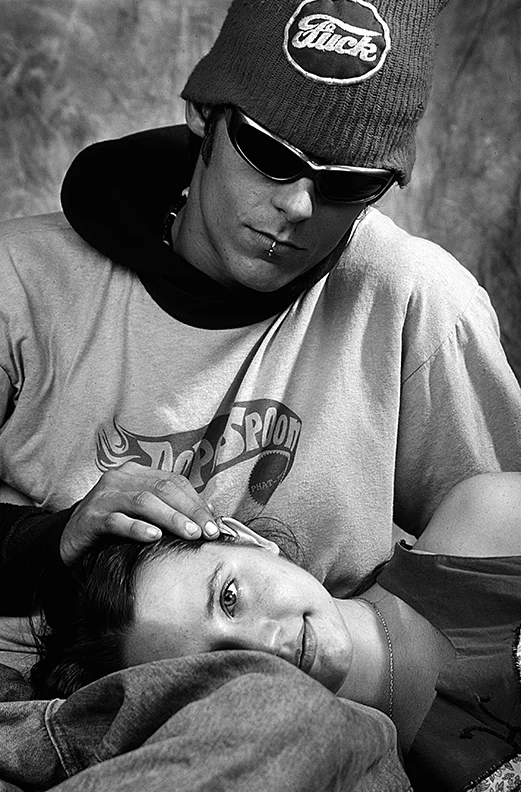

c. Jimmy Fishbein, 1996

Homelessness is a social occurrence that is multifaceted and difficult to associate with any one causal factor. Simply put, homelessness occurs when a household is not able to acquire or maintain housing, and this can occur for many reasons. Some of the most common reasons include financial hardship, disability, medical conditions, drug/alcohol addiction, and personal choice—among many others. In places where homelessness is most common, such as urban spaces, the social phenomenon is closely related to the cost of living, and the overall ability to acquire housing. According to the National Alliance to end Homelessness, as of January 2015, 564,708 people were homeless on a given night in the United States. Approximately 37% of these individuals were considered apart of a family group, while 63% were alone. As such, many national homelessness projects are focused on family, youth, and those with Veteran status.

c. Jimmy Fishbein, 1996

Many photography projects have focused on homelessness in the United States, such as Chuck Jine’s work on the Chicago Homeless, Steve Huff’s series entitled “My Homeless Project,” Martin Schoeller’s photography of LA’s homeless population, or unbelievable “I Photograph the Homeless by Becoming One Of Them” by Lee Jeffries. Just as these incredible photographers decided to focus their attention on photographing homeless populations in the United States, so too did Jimmy Fishbein undertake this project as a photography student in Santa Barbra—one of the first “out of the box” social photography projects that he did in his career.

c. Jimmy Fishbein, 1996

When Fishbein was in Santa Barbara for photography school, it was really the first time he was living and experiencing life outside of the Midwest, and as a part of a school-related project he became immediately interested in the homeless community within this pristine beach-front city. He claims that he was taken-back at the sheer number of homeless individuals in this space—in a large city, it is easier to understand that there would be a significant homeless population (like I mentioned above, the pricing of housing and poverty/unemployment rates alone can be enough to influence this). However, he realized during the execution of this personal project that the environment is much fairer than somewhere like Chicago in winter, for those living without a home. Many homeless individuals do try to live in these small beach cities for environmental reasons.

c. Jimmy Fishbein, 1996

Fishbein interviewed people old and young, and stated that the circumstances of the homelessness itself varied greatly. He spoke with many different individuals and took photos over the course of several months, from young people who claimed they just wanted to “live freely”, to older adults who were disabled veterans. Like most of the photography projects I mentioned above, Fishbein claims that “you have to be in it” spending time in the communities you work in, and really developing a sense of what life is like for these individuals—trying to capture their story, visually. Thus, it might be said that photography projects, which depict struggling subjects, can be divided into two categories: projects that listen to the participant’s life stories and try to capture the realities of everyday life, and those that purely use the subject for artistic interest. One is a social project, and one is a project which, intentionally or unintentionally, exploits the subject without consent—without true understanding.

c. Jimmy Fishbein, 1996

Photography helps to demonstrate the struggles, characters, and emotions of individuals who are living on the streets. Some of these projects develop out of activism, while others develop out of independent interest and the desire to tell a story. Regardless of how it emerges, one thing is for sure; looking at these portraits creates a reaction and evokes a desire to assign value or meaning within the viewer.

c. Jimmy Fishbein, 1996

Indyweek.com put out an article a few years back on how people “react” to seeing homeless individuals on the street. The author took a photo of a homeless individual, asleep, and then wrote about her ethical dilemma regarding whether or not to post and develop content around it. As an anthropologist, I feel strongly that participants in research, photography, or other projects of representation should absolutely give informed consent before they are used as a “subject.” Most of the photographers I’ve cited in this piece, Fishbein included, did gain consent from their photography participants—since they were awake and engaged in the act of being photographed. Many of these photographers also spent a great deal of time in the communities they worked. The author, Lisa Sorg, does mention that legally individuals can be photographed in public spaces without consent (whether or not this should be the case is up for discussion), and that her intent was to capture an image that would promote social justice:

“People need to be reminded that the homeless live among us; they are among society's the most vulnerable people. The way this man was sitting, his arms tucked inside his sweatshirt, his knees together and legs splayed—and the fact that he was sleeping—shows that vulnerability. From an artistic standpoint, I found him beautiful. I did not want to exoticize or romanticize him, just to show him honestly. Most people are beautiful when they're sleeping, and he is no different.”

It is not my goal to pass a value judgment here, although I personally would not support taking photos of sleeping individuals without consent as a researcher. Sorg does make a reasonable point about giving the “unseen” visibility, or creating visual depictions of vulnerable subjects for the world to see. Yet, his vulnerability was not something he agreed to have captured or put on display for the world to see. Unlike awake and consenting participants in these other projects, he is purely the object of display, with the artist’s meaning placed onto his image. His own perspective as a subject is not considered. It is possible that he did not feel vulnerable sleeping in that position whatsoever, and that rather, it was his nightly routine which has become so commonplace that he actually experiences a certain amount of comfort. I am speculating here, but without speaking to him and telling his story, we can never really know what is truly being depicted in this photograph.

c. Jimmy Fishbein, 1996

The final question I want to provoke is, what do these images do? Why are we captivated by suffering, struggle, and human experience in photography? It cannot be purely for activist goals—but perhaps to display a range of human possibilities and conditions. In the online environment, photography websites and blogs have the ability to gain more attention than ever, so what does showing a homeless series do? Ultimately, series like these have the ability to display circumstances of the “subject.” Human experiences, however far removed we may be from them, can evoke emotion, and these feelings are embodied in the way we go and treat others in the world. So perhaps all of these projects, sleeping or awake, young or old, urban or beach-town, do have something in common after all—they provide visual depictions of human experience. They show homeless circumstances by capturing refined details of the subjects themselves. These images shine light on places often ignored or unseen, and this can actually allow viewers to acknowledge our connectedness to the world of individuals around us, regardless of condition or location.

c. Jimmy Fishbein, 1996

By: Megan Melissa Machamer

MA Social Science, University of Chicago

BA Sociocultural Anthropology, UC San Diego

Megan Machamer is a sociocultural anthropologist who develops creative commentary for the Jimmy Fishbein photography blog. Her perspective as a social scientist contributes additional dialogue to stand-along photography and serves as one perspective to evoke thought and conversation upon viewing these photos.